Tracheostomy

Tracheostomy, the making of an opening into the trachea, has been practised

since the first century BC, and is a procedure with which all doctors

should be familiar.

INDICATIONS

Indications for tracheostomy may be classified as follows:

1 conditions causing upper airway obstruction;

2 conditions necessitating protection of the tracheobronchial tree;

3 conditions causing respiratory failure.

Protection of the tracheobronchial tube

Any condition causing pharyngeal or laryngeal incompetence may allow aspiration

of food, saliva, blood or gastric contents. If the condition is of short

duration, e.g. general anaesthesia, endotracheal intubation is appropriate,

but for chronic conditions tracheostomy is necessary. It allows easy access

to the trachea and bronchi for regular suction and permits the use of a

cuffed tube, which affords further protection against aspiration. Examples

of such conditions are:

1 polyneuritis (e.g. Guillain–Barré syndrome);

2 bulbar poliomyelitis;

3 multiple sclerosis;

4 myasthenia gravis;

5 tetanus;

6 brain-stem stroke;

7 coma due to:

(a) head injury;

(b) poisoning;

(c) stroke;

(d) cerebral tumour;

(e) intracranial surgery (unless the state of coma is likely to be prolonged,

endotracheal intubation is preferable in the first place);

8 multiple facial fractures.

Respiratory failure

Tracheostomy in cases of respiratory failure allows:

1 reduction of dead space by about 70 mL (in the adult);

2 bypass of laryngeal resistance;

3 access to the trachea for the removal of bronchial secretions;

4 administration of humidified oxygen;

5 positive-pressure ventilation when necessary.

Respiratory failure is often multifactorial and may be considered under the

following headings.

UPPER AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Congenital

1 Subglottic or upper tracheal stenosis.

2 Laryngeal web.

3 Laryngeal and vallecular cysts.

4 Tracheo-oesophageal anomalies.

5 Haemangioma of larynx.

Trauma

1 Prolonged endotracheal intubation.

2 Gunshot wounds and cut throat, laryngeal fracture.

3 Inhalation of steam or hot vapour.

4 Swallowing of corrosive fluids.

5 Radiotherapy (may cause oedema).

Infections

1 Acute epiglottitis (see Chapter 33).

2 Laryngotracheobronchitis.

3 Diphtheria.

4 Ludwig’s angina.

Malignant tumours

1 Advanced malignant disease of the tongue, larynx, pharynx or upper trachea.

2 As part of a surgical procedure for the treatment of laryngeal cancer.

3 Carcinoma of thyroid.

Bilateral laryngeal paralysis

1 Following thyroidectomy.

2 Bulbar palsy.

3 Following oesophageal or heart surgery.

Foreign body

1 Remember the Heimlich manoeuvre — grasp the patient from behind with a fist in

the epigastrium and apply sudden pressure upwards towards the diaphragm. It may

need to be repeated several times before the foreign body is expelled.

Box 39.1 Upper airway obstruction.

1 Pulmonary disease—exacerbation of chronic bronchitis and emphysema;

severe asthma; postoperative pneumonia from accumulated

secretions.

2 Abnormalities of the thoracic cage—severe chest injury (flail chest);

ankylosing spondylitis; severe kyphosis.

3 Neuromuscular dysfunction—e.g. Guillain–Barré syndrome; tetanus;

motor neurone disease; poliomyelitis.

Criteria for performing tracheostomy

Tracheostomy should, whenever possible, be carried out as an elective

procedure and not as a desperate last resort.There are degrees of urgency.

1 If the patient has life-threatening airway obstruction when first seen, it

is obvious that urgent treatment is required. If endotracheal intubation fails,

tracheostomy must be done at once.There is no time for sterility—with the

left hand, hold the trachea on either side to immobilize it, make a vertical incision

through the tissues of the neck into the trachea and twist the blade

through 90° to open up the trachea.There will be copious dark bleeding but

the patient will gasp air through the opening. Using the index finger of the

left hand as a guide in the wound, try to insert some sort of tube into the trachea.

The blood should then be sucked out by whatever means are available.

Once an airway is established, the tracheostomy can be tidied up under

more controlled conditions.

2 In patients with airway obstruction of more gradual onset, do not allow

the situation to deteriorate to that described above. Stridor, recession and

tachycardia denote the need for intervention, and cyanosis and bradycardia

indicate that you are running out of time.The case should be discussed with

an experienced anaesthetist, and the patient taken to the operating theatre.

The ideal is to carry out tracheostomy under general anaesthesia with endotracheal

intubation. Once a tube has been inserted, the airway is safe and

the tracheostomy can be performed calmly and carefully with full sterile

precautions. If the anaesthetist is unable to intubate the patient, it will be

necessary to perform the operation under local anaesthetic using infiltration

with lignocaine. The anaesthetist meanwhile will administer oxygen

through a face-mask.

3 Elective tracheostomy should be carried out before deterioration

occurs in non-obstructive cases as listed above and patients who have

previously been intubated because of obstruction or for ventilation but

who cannot be extubated safely.

Such elective tracheostomy cases are ideal for trainees to learn the technique

of the operation safely under supervision and every such opportunity should be taken.

Dictum

In cases of respiratory obstruction and respiratory failure and in the

absence of steady improvement, support the airway by tracheostomy or

endotracheal intubation.

Remember that children may deteriorate with dramatic suddenness.

THE OPERATION OF ELECTIVE TRACHEOSTOMY

Like any other operation, tracheostomy can be learned only by instruction

and practice, so that only a brief description will be given.

The operation should be carried out under general anaesthesia with

endotracheal intubation. The neck should be extended and the head must

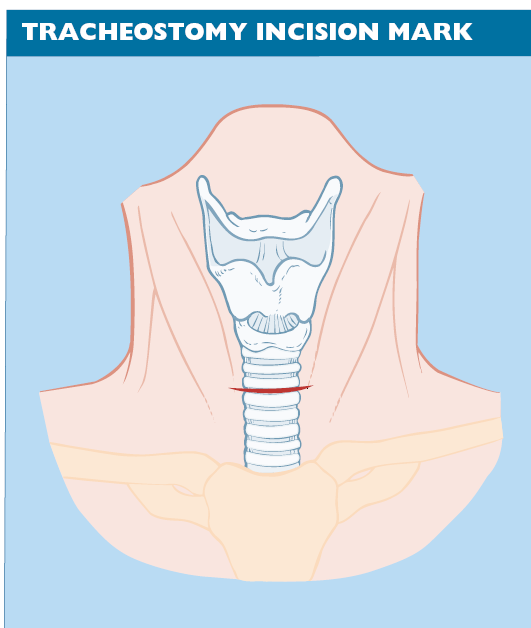

be straight, not turned to one side. A transverse incision is preferable to a

vertical incision, and should be centred midway between the cricoid cartilage

and sternal notch (Fig. 39.1). The strap muscles are identified and retracted

laterally (Fig. 39.2) and the thyroid isthmus is divided. Once the

trachea has been reached (it is always deeper than you expect), the cricoid

must be identified by palpation and the tracheal rings counted. An opening

is made into the trachea, centred on the third and fourth rings (Fig. 39.3).

In adults, an ellipse of sufficient size to accept the tracheostomy tube is

excised, but in children, a single slit in the tracheal wall is preferable, after first inserting stay sutures on either side to allow traction on the opening

in order to insert the tube.

After insertion of the tracheostomy tube, the trachea is aspirated thoroughly

and unless the skin incision has been excessively long it is left unsutured.

To sew the wound tightly makes surgical emphysema more likely and replacement of the tube more difficult.

Choice of tracheostomy tube

The choice of tube depends on the reason for the tracheostomy.

1 In cases of airway obstruction, a silver tube such as the Negus is ideal. It

has an inner tube, which can be removed for cleaning, and has an expiratory

flap-valve (sometimes called a speaking valve) to allow phonation.

2 In cases requiring ventilation or protection from aspirated secretions, a

cuffed tube is necessary.The day of the red rubber tube has gone, and inert

plastic tubes are now used.The cuff should be of a low-pressure design to

prevent stricture formation.

3 Small children should never be fitted with a cuffed tube because of the

risk of causing stenosis. A plain silastic tube should be used initially, and if

ventilation is not required it can be changed at a later date to a silver tube

fitted with an optionally valved inner tube (e.g. Sheffield tracheostomy

tube). It is beyond the scope of this book to consider in detail the indications

for metal or plastic tubes.

After-care of the tracheostomy

Nursing care

Nursing care must be of the highest standard to keep the tube patent and

prevent dislodgement.

Position

Adult patients in the postoperative period should usually be sitting well

propped up; care must be taken in infants that the chin does not occlude the

tracheostomy and the neck should be extended slightly over a rolled-up

towel.

Suction

Suction is applied at regular intervals dictated by the amount of secretions

present. A clean catheter must be passed down into the tube in conscious

patients. Unconscious or ventilated patients will require deeper suction

and physiotherapy.

Humidification

Humidification of the inspired air is essential to prevent drying and the formation

of crusts and is achieved by any conventional humidifier. Remember

that the humidity you can see is due to water droplets, not vapour, and may waterlog small infants.

Avoidance of crusts

Avoidance of crusts is aided by adequate humidification; if necessary, sterile

saline (1 mL) can be introduced into the trachea, followed by suction.

Tube changing

Tube changing should be avoided if possible for 2 or 3 days, after which the

track should be well established and the tube can be changed easily. Meanwhile,

if a silver tube has been inserted, the inner tube can be removed and

cleaned as often as necessary. Cuffed tubes need particular attention, with

regular deflation of the cuff to prevent pressure necrosis.The amount of air

in the cuff should be the minimum required to prevent an air leak.

Decannulation

Decannulation should only be carried out when it is obvious that the tracheostomy

is no longer required. The patient should be able to manage

with the tube occluded for at least 24 h before it is removed (Fig. 39.4).

Decannulation in children often presents particular difficulties. After decannulation,

the patient should remain in hospital under observation for

several days.

Complications

Periochondritis and subglottic stenosis

Periochondritis and subglottic stenosis may result, especially if the cricoid cartilage is injured. Go below the first ring.

Mediastinal emphysema or pneumothorax

Mediastinal emphysema or pneumothorax may occur after a very low tracheostomy,

or if the tube becomes displaced into the pretracheal space.The

chest should be X-rayed after operation.

Obstruction

Obstruction of the tube or trachea by crusts of inspissated secretion may

prove to be fatal. If the airway becomes obstructed and cannot be cleared by

suction, act boldly. Remove the whole tube and replace it if blocked. If the

tube is patent, explore the trachea with angled forceps to remove the obstruction.

An explosive cough may expel the crust and the tube can then be

replaced.

Complete dislodgement

Complete dislodgement of the tube may occur if it is not adequately fixed.

Hold the wound edges apart with a tracheal dilator and put in a clean tube.

A good light is essential.

Partial dislodgement

Partial dislodgement of the tube is more difficult to recognize and may be

fatal. The tube comes to lie in front of the trachea, the airway will be impaired

and, if left, erosion of the innominate artery may result in catastrophic

haemorrhage. Make sure that at all times the patient breathes

freely through the tube, and such an occurrence should be avoided. Surgical

emphysema of startling severity may occur if the patient is on positivepressure

ventilation.

It is common experience that as soon as a tracheostomy has been performed

there is pressure from all concerned to close it. A tracheostomy must be retained until you are sure it is no longer necessary.