Facial Nerve Paralysis

Paralysis of the facial nerve is a subject of fascination to the otologist and

a cause of distress to the patient. Owing to its frequency and diversity of

aetiology, it is a matter of very considerable importance to workers in all

spheres of medical life.

The causes are numerous and are considered in Table 16.1.

DIAGNOSIS

The patient presents with a varying degree of weakness of the facial muscles

and sometimes difficulty in clearing food from the bucco gingival sulcus as a

result of buccinator paralysis.

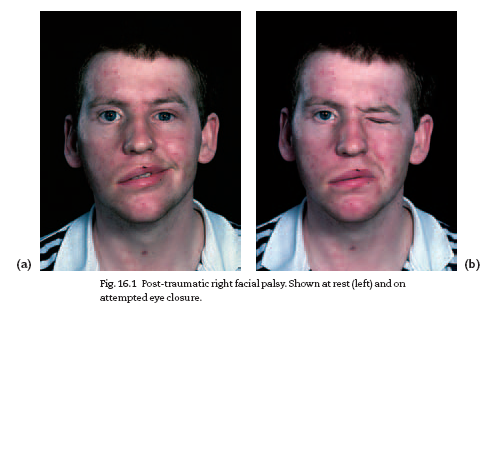

Facial asymmetry is accentuated by attempting to close the eyes tightly,

to show the teeth or to whistle (Fig. 16.1).

It is important to remember that in supranuclear lesions the movements

of the upper part of the face are likely to be unaffected as the forehead

muscles have bilateral cortical representation.Moreover, involuntary movements

(e.g. smiling) may be retained even in the lower face. A most careful

history and aural and neurological examination are essential, including attention

to such matters as impaired taste (lesion is above origin of chorda tympani),

hyperacusis with loss of the stapedius reflex (lesion is above nerve to

stapedius) or reduction of lacrimation (lesion is above geniculate ganglion).

Electrodiagnosis is used in the assessment of the degree of involvement

of the nerve and includes nerve conduction tests and electromyography.

A detailed description of the various tests is beyond the scope

of this volume, but their application is of value as a guide to prognosis and

management.

palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis)

Bell’s palsy is a lower motor neurone facial palsy of unknown cause, but possibly

viral. It is part of the group of idiopathic cranial mono-neuropathies.

Bell’s palsy may be complete or incomplete; the more severe the palsy,

the worse the prognosis for recovery. In practice, full recovery may be

expected in 85% of cases.The remainder may develop complications, such

as ectropion or synkinesis.

CAUSES OF FACIAL NERVE PARALYSIS

Supranuclear and nuclear

Cerebral vascular lesions

Poliomyelitis

Cerebral tumours

Infranuclear

Bell’s palsy

Trauma (birth injury, fractured temporal bone, surgical)

Tumours (acoustic neurofibroma,parotid tumours, malignant disease of

the middle ear)

Suppuration (acute or chronic otitis media)

Ramsay Hunt syndrome

Multiple sclerosis

Guillain–Barré syndrome

Sarcoidosis

Table16.1 Causes of facial nerve paralysis.

TREATMENT

Treatment of Bell’s palsy should not be delayed.

1 Prednisolone given orally is the treatment of choice, but only if started

in the first 24 h. In an adult, start with 80 mg daily and reduce the dose

steadily to zero over a period of 2 weeks.

2 Surgical decompression of the facial nerve is a matter of controversy:

some authorities decompress at an early stage: most do not advise

decompression.

3 Tarsorrhaphy may be needed to protect the cornea of the unblinking

eye.

4 In the rare event of recovery not taking place, cross-facial grafting or

hypoglossal–facial anastomosis may be carried out to restore symmetry to

the face.

5 Inward collapse of the cheek can be disguised with a built-up denture to

restore the contour.

Do not make a diagnosis of Bell’s palsy until you have excluded

other causes. If recovery does not take place in 6 months, reconsider

the diagnosis.

Ramsay Hunt syndrome

This is due to herpes zoster infection of the geniculate ganglion, affecting

more rarely the IX and X nerves and, very occasionally, the V, VI or XII.The

patient is usually elderly, and severe pain precedes the facial palsy and

the herpetic eruption in the ear (sometimes on the tongue and palate).The

patient usually has vertigo, and the hearing is impaired. Recovery of

facial nerve function is much less likely than in Bell’s palsy.

Prompt treatment with acyclovir given orally may improve the prognosis

and reduce post-herpetic neuralgia.

Facial palsy in acute or chronic otitis media

This requires immediate expert advice, as urgent surgical treatment is

usually necessary.

Traumatic facial palsy

This may result from fracture of the temporal bone or from ear surgery. If

the onset is delayed, recovery is to be expected but if there is immediate

palsy, urgent surgical exploration and decompression or grafting will be

required. Otological advice should be sought without delay