Deafness

Attention has already been drawn to the two major categories of

deafness—conductive and sensorineural. The distinction is easily made by

tuning fork tests, which should never be omitted.

CAUSES

There is no strict order in the list featured in Table 4.1, because the frequency

with which various causes of deafness occur varies from one community

to another and from one age group to another.Nevertheless, some

indication is given by division into ‘more common’ and ‘less common’

groups. Always try to make a diagnosis of the cause of deafness and start by

deciding whether it is conductive or sensorineural.

MANAGEMENT

The management of a number of specific conditions will be dealt with in

subsequent chapters but some general comments are appropriate.

deaf child

Early diagnosis of deafness in the infant is essential if irretrievable developmental

delay is to be avoided.The health visitor should screen all babies at

about 8 months of age and those failing a routine test must be referred to a

specialist audiological centre without delay for more thorough investigation.

Some babies are ‘at risk’ of deafness and are tested as soon after birth

as possible.They include those affected by:

1 prematurity and low birth-weight;

2 perinatal hypoxia;

3 Rhesus disease;

4 family history of hereditary deafness;

5 intrauterine exposure to viruses such as rubella, cytomegalovirus and

HIV.

The testing of babies suspected or at risk of being deaf is very specialized.

The mother’s assessment is very important and should always be taken seriously.

She is likely to be right if she thinks her child’s hearing is not normal.

Testing of ‘at risk’ babies in the neonatal period is now carried out in many

centres by the recording of otoacoustic emissions (see Chapter 3).

Conductive Sensorineural

More common

Wax Presbycusis (deafness of old age)

Acute otitis media Noise-induced (prolonged exposure to high

noise level, industrial deafness, chronic otitis

media disco music)

Barotrauma Congenital (maternal rubella, cytomegalovirus,

Otosclerosis toxoplasmosis, hereditary deafness,anoxia,

jaundice,congenital syphilis)

Injury of the tympanic membrane Drug-induced (aminoglycoside antibiotics,

aspirin, quinine, some diuretics, some beta

blockers)

Menière’s disease

Late otosclerosis

Infections (CSOM,mumps,herpes zoster,

meningitis, syphilis)

Less common

Traumatic ossicular dislocation Acoustic neuroma

Congenital atresia of the external Head injury

canal

Agenesis of the middle ear CNS disease (multiple sclerosis, metastases)

Tumours of the middle ear Metabolic (diabetes,hypothyroidism,

Paget’s disease of bone)

Psychogenic

Unknown aetiology

Sudden sensorineural deafness

Sudden sensorineural deafness is an otological emergency and should be

treated as seriously as would be sudden blindness. Immediate admission to

hospital should be arranged, as delay may mean permanent deafness.

Sudden deafness may be unilateral or bilateral and most cases are regarded

as being viral or vascular in origin. Investigation may fail to show a

cause and treatment is usually with low-molecular-weight dextran, steroids

and inhaled carbon dioxide. Bilateral profound deafness, especially if of sudden

onset, is a devastating blow and for this reason various organizations

exist to give advice and support.

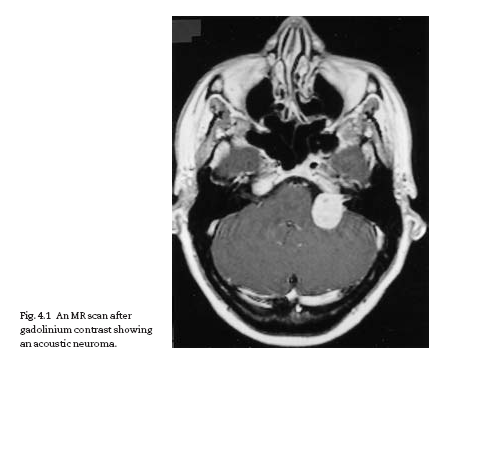

Vestibular Schwannoma (Acoustic neuroma)

Vestibular Schwannoma is a benign tumour of the superior vestibular nerve in

the internal auditory meatus or cerebello-pontine (CP) angle. It is usually

unilateral, except in familial neurofibromatosis (NF2), when it may be bilat-eral. In its early stages, it causes a progressive hearing loss and some imbalance.

As it enlarges, it may encroach on the trigeminal nerve in the CP angle,

causing loss of corneal sensation. In its advanced stage, there is raised intracranial

pressure and brain stem displacement. Early diagnosis reduces

the morbidity and mortality of operations. Unilateral sensorineural deafness

should always be investigated to exclude a neuroma. Audiometry will

confirm the hearing loss. MR scanning will identify even small tumours with

certainty (Fig. 4.1).

Hearing aids

In cochlear forms of sensorineural deafness, loudness recruitment is often

a marked feature. This results in an intolerance of noise above a certain

threshold, and makes the provision of amplification very difficult.

The choice of hearing aids is now large. Most are worn behind the ear

with a mould fitting into the meatus. If the mould does not fit well, oscillatory

feedback will occur and the patient will not wear the aid. More sophisticated

(and expensive) are the ‘all-in-the-ear’ aids, where the electronics

are built into a mould made to fit the patient’s ear. They give good directional

hearing and, because they are individually built, the output can bematched to the patient’s deafness. The current generation of hearing aids

are digital, allowing more refinement in the sound processing and more

control of the aid.

A recent development has been the bone-anchored hearing aid

(BAHA). A titanium screw is threaded into the temporal bone and allowed

to fuse to the bone (osseo-integration). A transcutaneous abutment then

allows the attachment of a special hearing aid that transmits sound directly

by bone conduction to the cochlea.The main application of BAHA is to patients

with no ear canal, or chronic ear disease, who are unable to wear a

conventional aid and is much more effective than the old-fashioned bone

conductor aid.

Cochlear implants

Much research has been done, both in the USA and Europe, on the implantation

of electrodes into the cochlea to stimulate the auditory nerve.The

apparatus consists of a microphone, an electronic sound processor and a

single or multichannel electrode implanted into the cochlea. Cochlear implantation

is only appropriate for the profoundly deaf. Results, particularly

with an intracochlear multichannel device, can be spectacular, with some

patients able to converse easily. Most patients obtain a significant improvement

in their ability to communicate and implantation has been extended

for use in children. It is no longer an experimental procedure but a valuable

therapeutic technique.

Lip-reading

Instruction in lip-reading is carried out much better while usable hearing

persists and should always be advised to those at risk of total or profound

deafness.

Electronic aids for the deaf

Amplifying telephones are easily available to the deaf and telephone companies

usually provide willing advice. Many modern hearing aids are fitted with

a loop inductance system to make the use of telephones easier.

Various computerized voice analysers that give a rapid visual display are

also available, but these require the services of a skilled operator and are

still in the developmental phase. Automatic voice recognition machines maytake over this role in the foreseeable future.