Complications of Middle-Ear Infection

Acute mastoiditis

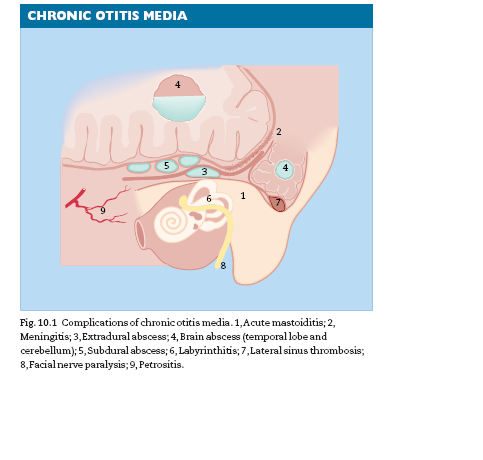

Acute mastoiditis is the result of extension of acute otitis media into the

mastoid air cells with suppuration and bone necrosis. Common in the

preantibiotic era, it is now rare in theWestern world (Fig. 10.1).

SYMPTOMS

1 Pain—persistent and throbbing.

2 Otorrhoea—usually creamy and profuse.

3 Increasing deafness.

SIGNS

1 Pyrexia.

2 General state—the patient is obviously ill.

3 Tenderness is marked over the mastoid antrum.

4 Swelling in the postauricular region, with obliteration of the sulcus.The

pinna is pushed down and forward (Fig. 10.2).

5 Sagging of the meatal roof or posterior wall.

6 The tympanic membrane is either perforated and the ear discharging,

or it is red and bulging.

If the tympanic membrane is normal, the patient does not have acute

mastoiditis.

INVESTIGATIONS

1 White blood count—raised neutrophil count.

2 CT scanning shows opacity and air cell coalescence.

OCCASIONAL FEATURES OF ACUTE MASTOIDITIS

1 Subperiosteal abscess over the mastoid process.

2 Bezold’s abscess—pus breaks through the mastoid tip and forms an

abscess in the neck.

3 Zygomatic mastoiditis—results in swelling over the zygoma.

TREATMENT

When the diagnosis of acute mastoiditis has been made, do not delay.The

patient should be admitted to hospital.

1 Antibiotics should be administered intravenously (i.v).The choice of antibiotic,

as always, depends on the sensitivity of the organism. If the organism

is not known and there is no pus to culture, start amoxycillin and

metronidazole immediately.

2 Cortical mastoidectomy. If there is a subperiosteal abscess or if the response

to antibiotics is not rapid and complete, cortical mastoidectomy

must be performed.The mastoid is exposed by a postaural incision and the

cortex is removed by drilling. All mastoid air cells are then opened, removing

pus and granulations. The incision is closed with drainage. The object

of this operation is to drain the mastoid antrum and air cells but leave the

middle ear, the ossicles and the external meatus untouched.

Meningitis

CLINICAL FEATURES

1 The patient is unwell.

2 Pyrexia—may only be slight.

3 Neck rigidity.

4 Positive Kernig’s sign.

5 Photophobia.

6 Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—lumbar puncture essential unless there is

raised intracranial pressure (q.v).

(a) Often cloudy.

(b) Pressure raised.

(c) White cells raised.

(d) Protein raised.

(e) Chloride lowered.

(f) Glucose lowered.

(g) Organisms present on culture and Gram stain.

TREATMENT

1 Do not give antibiotic until CSF has been obtained for culture and confirmation

of diagnosis.Then start penicillin parenterally and intrathecally.

2 Mastoidectomy is necessary if meningitis results from mastoiditis and

should not be delayed.The type of operation will be dictated by the extent

and nature of the ear disease.

Extradural abscess

An abscess formed by direct extension either above the tegmen or around

the lateral sinus (perisinus abscess).

The features of mastoiditis are present and often accentuated. Severe

pain is common.The condition may only be recognized at operation.

In addition to antibiotics, mastoid surgery is essential to treat the underlying

ear disease and drain the abscess.

Brain abscess

Otogenic brain abscess may occur in the cerebellum or in the temporal

lobe of the cerebrum.The two routes by which infection reaches the brain

are by direct spread via bone and meninges or via blood vessels, i.e.

thrombophlebitis.

A brain abscess may develop with great speed or may develop more

gradually over a period of months.The effects are produced by:

1 systemic effects of infection, i.e. malaise, pyrexia—which may be absent;

2 raised intracranial pressure, i.e. headache, drowsiness, confusion, impaired

consciousness, papilloedema;

3 localizing signs.

TEMPORAL LOBE ABSCESS

Localizing signs (Fig. 10.3):

1 dysphasia—more common with left-sided abscesses;

2 contralateral upper quadrantic homonymous hemianopia;

3 paralysis—contralateral face and arm, rarely leg;

4 hallucinations of taste and smell.

CEREBELLAR ABSCESS

Localizing signs:

1 neck stiffness;

2 weakness and loss of tone on same side;

3 ataxia—falling to same side;

4 intention tremor with past-pointing;

5 dysdiadokokinesis;

6 nystagmus—coarse and slow;

7 vertigo—sometimes.

DIAGNOSIS OF INTRACRANIAL SEPSIS:

1 Any patient with chronic ear disease who develops pain or headache

should be suspected of having intracranial extension.

2 Any patient who has otogenic meningitis, labyrinthitis or lateral sinus

thrombosis may also have a brain abscess.

3 Lumbar puncture may be dangerous owing to pressure coning.

4 Neurosurgical advice should be sought at an early stage if intracranial

suppuration is suspected.

5 Confirmation and localization of the abscess will require further

investigation.

Computerized tomography (CT) scanning will demonstrate intracranial

abscesses reliably and should always be performed when it is suspected.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging shows soft-tissue lesions with more detail

than CT but gives no bone detail. If in doubt what to do, discuss the problem with a radiologist.

TREATMENT

It is the brain abscess that will kill the patient, and it is this that must take surgical

priority.The abscess should be drained through a burr hole, or excised

via a craniotomy and then, if the patient’s condition permits, mastoidectomy

should be performed under the same anaesthetic. After pus has been

obtained for culture, aggressive therapy with antibiotics is essential, to be

amended as necessary when the sensitivity is known.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis of brain abscess has improved with the use of antibiotics and

modern diagnostic methods but still carries a high mortality; the outlook is

better for cerebral abscesses than cerebellar, in which the mortality rate

may be 70%. Left untreated, death from brain abscess occurs from pressure

coning, rupture into a ventricle or spreading encephalitis.

Subdural abscess

Subdural abscess more commonly occurs in the frontal region from

sinusitis, but may result from ear disease. Focal epilepsy may develop from

cortical damage.The prognosis is poor.

Labyrinthitis

Infection may reach the labyrinth by erosion of a fistula by cholesteatoma. It

may rarely arise in acute otitis media.

CLINICAL FEATURES

1 Vertigo may be mild in serous labyrinthitis or overwhelming in purulent

labyrinthitis.

2 Nausea and vomiting.

3 Nystagmus towards the opposite side.

4 There may be a positive fistula test—pressure on the tragus causes

vertigo or eye deviation by inducing movement of the perilymph.

5 There will be profound sensorineural deafness in purulent labyrinthitis.

TREATMENT

1 Antibiotics.

2 Mastoidectomy for chronic ear disease.

3 Occasionally, labyrinthine drainage.

Lateral sinus thrombosis

A perisinus abscess from mastoiditis causes thrombosis of the lateral sinus

and ascending cortical thrombo-phlebitis. Septic emboli are given off and

metastatic abscesses may occur. The prognosis is poor but improved by

early diagnosis and treatment.

CLINICAL FEATURES

1 Swinging pyrexia—up to 40°C.

2 Rigors.

3 Polymorph leucocytosis.

4 Positive Tobey–Ayer test—sometimes. Compression of contralateral

internal jugular vein Æ rise in CSF pressure. Compression of ipsilateral

internal jugular vein Æno rise.

5 Meningeal signs—sometimes.

6 Positive blood cultures, especially if taken during a rigor.

7 Papilloedema—sometimes.

8 Metastatic abscesses—prognosis poor.

9 Cortical signs—facial weakness, hemiparesis.

TREATMENT

1 Antibiotics.

2 Mastoidectomy with wide exposure of the lateral sinus and even

removal of infected thrombus.

Facial paralysis

Facial paralysis can result from both acute and chronic otitis media.

1 Acute otitis media—especially in children and especially if the facial

nerve canal in the middle ear is dehiscent. It is, however, uncommon.

2 Chronic otitis media—cholesteatoma may erode the bone around the

horizontal and vertical parts of the facial nerve, and infection and granulations

cause facial paralysis.

In the early stages, the patient will complain of dribbling from the corner of

the mouth. Clinical examination confirms the diagnosis—it may be difficult

to detect if the weakness is minimal.

TREATMENT

If due to acute otitis media, a full recovery with antibiotic therapy is to be

expected.

If due to CSOM, mastoidectomy is mandatory, with clearance of disease

from around the facial nerve.

Remember—a facial palsy occurring in the presence of chronic ear disease is

not Bell’s palsy and active treatment is needed if the palsy is not to become

permanent. Do not give steroids.

Petrositis

Very rarely, infection may spread to the petrous apex and involve the VIth

cranial nerve.

CLINICAL FEATURES (GRADENIGO’S SYNDROME):

1 Diplopia from lateral rectus palsy.

2 Trigeminal pain.

3 Evidence of middle-ear infection.

TREATMENT

1 Antibiotics.

2 Mastoidectomy with drainage of the apical cells.