MEASUREMENT OF PLANT DISEASE AND OF YIELD LOSS

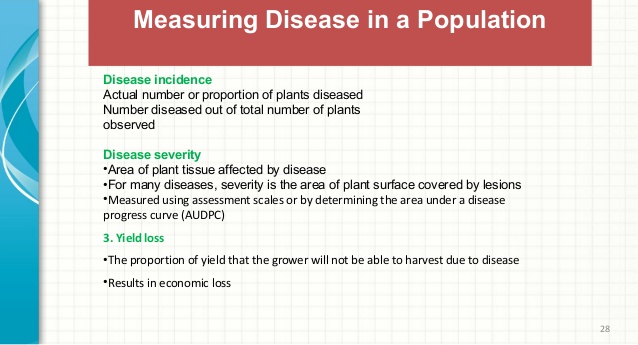

When measuring disease, one is interested in measuring (1) the incidence of the disease, i.e., the number or proportion of plant units that are diseased (i.e., the number or proportion of plants, leaves, stems, and fruit that show any symptoms) in relation to the total number of units examined; (2) the severity of the disease, i.e., the proportion of area or amount of plant tissue that is diseased; and (3) the yield loss caused by the disease, i.e., the proportion of the yield that the grower will not be able to harvest because the disease destroyed it directly or prevented the plants from producing it (the yield loss is the difference between attainable yield and actual yield).

Measuring disease incidence is relatively quick and easy, and this measurement is the one that is used commonly in epidemiological studies to measure the spread of a disease through a field, region, or country. In a few cases, such as cereal smuts, neck blast of rice, brown rot of stone fruits, and the vascular wilts of annuals, disease incidence has a direct relationship to the severity of the disease and yield loss because each diseased plant or fruit is a total loss. However, in many other diseases (such as most leaf spots, root lesions, and rusts) in which plants are counted as diseased whether they are exhibiting a single lesion or hundreds of lesions, disease incidence may have little relationship to the severity of the disease or to yield loss. Although severity and yield loss are of much greater importance to the grower than disease incidence, their measurement is more difficult and, in some cases, not possible until too late in the development of an epidemic.

Disease severity is usually expressed as the percentage or proportion of plant area or fruit volume destroyed by a pathogen. More often, disease assessment scales from 0 to 10 or 1 to 4 are used to express the relative proportions of affected tissue at a particular point in time. Yield loss due to disease is measured at a specific growth stage, from sequential disease assessments at several stages of a crop’s growth, or by determining the area under a disease progress curve (AUDPC), i.e., the area between the disease progress curve and the X axis of the graph.

The area under the disease progress curve is used to summarize the progress of disease severity and is calculated by a formula that takes into account the number of times the disease severity was evaluated, the disease severity at each evaluation time, and the time duration of the epidemic.

Yield loss almost always results in economic loss from disease. Economic loss occurs whenever economic returns from the crop decrease because of reduced yields, because of the cost of agricultural activities undertaken to reduce damage to the crop, or both. In managing plant diseases, however, the grower can justify applying disease control measures only when the incremental costs of control are generally smaller than the increase in crop returns. The level of disease, i.e., the amount of plant damage, at which control costs just equal incremental crop returns is called the economic threshold of the disease. The economic threshold of a crop–pathogen system varies with the tolerance level (damage threshold) of the crop, which depends on the growth stage of the crop when attacked, crop management practices, environment, shifts in pathogen virulence, and new control practices. The economic threshold also varies with changing commodity prices and control costs.