Environmental Factors that Affect Disease Epidemic

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS THAT AFFECT DEVELOPMENT OF EPIDEMICS

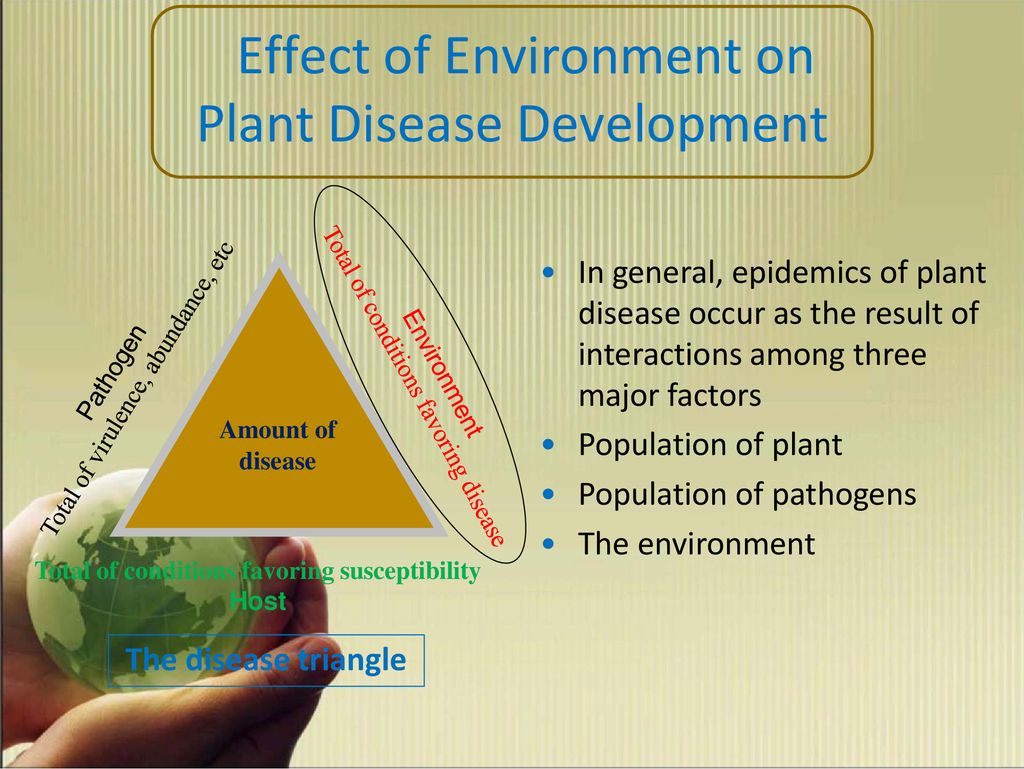

The majority of plant diseases occur wherever the host is grown but, usually, do not develop into severe and widespread epidemics. The concurrent presence in the same areas of susceptible plants and virulent pathogens does not always guarantee numerous infections, much less the development of an epidemic. This fact dramatizes the controlling influence of the environment on the development of epidemics. The environment may affect the availability, growth stage, succulence, and genetic susceptibility of the host plants. It may also affect the survival, vigor, rate of multiplication, sporulation, and ease, direction, and distance of dispersal of the pathogen, as well as the rate of spore germination and penetration. In addition, the environment may affect the number and activity of the vectors of the pathogen.

The most important environmental factors that affect the development of plant disease epidemics are moisture, temperature, and the activities of humans in terms of cultural practices and control measures.

Moisture

Abundant, prolonged, or repeated high moisture, whether in the form of rain, dew, or high humidity, is the dominant factor in the development of most epidemics of diseases caused by oomycetes and fungi (blights, downy mildews, leaf spots, rusts, and anthracnoses), bacteria (leaf spots, blights, soft rots), and nematodes. Moisture not only promotes new succulent and susceptible growth in the host, but, more importantly, it increases sporulation of fungi and multiplication of bacteria. Moisture facilitates spore release by many fungi and the oozing of bacteria to the host surface, and it enables spores to germinate and zoospores, bacteria, and nematodes to move. The presence of high levels of moisture allows all these events to take place constantly and repeatedly and leads to epidemics. In contrast, the absence of moisture for even a few days prevents all of these events from taking place so that epidemics are interrupted or stopped completely. Some diseases caused by soilborne pathogens, such as Fusarium and Streptomyces, are more severe in dry than in wet weather, but such diseases seldom develop into important epidemics.

Epidemics caused by viruses and mollicutes are affected only indirectly by moisture, primarily by the effect that higher moisture has on the activity of the vector. Moisture may increase the activity of some vectors, as happens with the fungal and nematode vectors of some viruses, or it may reduce the activity of the vectors, as happens with the aphid, leafhopper, and other insect vectors of some viruses and mollicutes. The activity of these vectors is reduced drastically in rainy weather.

Temperature

Epidemics are sometimes favored by temperatures higher or lower than the optimum for the plant because they reduce the plant’s level of partial resistance. At certain levels, temperatures may even reduce or eliminate the race-specific resistance of host plants. Plants growing at such temperatures become “stressed” and predisposed to disease, provided the pathogen remains vigorous.

Low temperature reduces the amount of inoculums of oomycete fungi, bacteria, and nematodes that survives cold winters. High temperature reduces the inoculums of viruses and mollicutes that survives hot summer temperatures. In addition, low temperatures reduce the number of vectors that survive the winter. Low temperatures occurring during the growing season can reduce the activity of vectors.

The most common effect of temperature on epidemics, however, is its effect on the pathogen during the different stages of pathogenesis, i.e., spore germination or egg hatching, host penetration, pathogen growth or reproduction, invasion of the host, and sporulation. When temperature stays within a favorable range for each of these stages, a polycyclic pathogen can complete its infection cycle within a very short time (usually in a few days). As a result, polycyclic pathogens can produce many infection cycles within a growing season. Because the amount of inoculum is multiplied manyfold (perhaps 100 times or more) with each infection cycle and because some of the new inoculum is likely to spread to new plants, more infection cycles result in more plants becoming infected by more and more pathogens, thus leading to the development of a severe epidemic.

In reality, moisture and temperature must be favorable and act together in the initiation and development of the vast majority of plant diseases and plant disease epidemics.