Development of Epidemics

Development of Epidemics

For a disease to become significant in a field, particularly if it is to spread over a large area and develop into a severe epidemic, specific combinations of environmental factors must occur either constantly or repeatedly, and at frequent intervals, over a large area. Even in a single, small field that contains the pathogen, plants almost never become severely diseased from just one set of favorable environmental conditions. It takes repeated infection cycles and considerable time before a pathogen produces enough individuals to cause an economically severe epidemic in the field. Once large populations of the pathogen are available, however, they can attack, spread to nearby fields, and cause a severe epidemic in a very short time, often in just a few days.

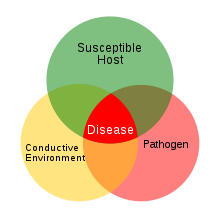

A plant disease epidemic can occur in a garden, a greenhouse, or a small field, but “epidemic” generally implies the development and rapid spread of a pathogen on a particular kind of crop plant cultivated over a large area, such as a large field, a valley, a section of a country, the entire country, or even part of a continent. Therefore, the first component of a plant disease epidemic is a large area planted to a genetically uniform crop plant, with the plants and the fields being close together. The second component of an epidemic is the presence or appearance of a virulent pathogen. Such cohabitations of host plants and pathogens occur, of course, daily in countless locations. Most of these, however, cause local diseases of varying severity, destroy crop plants to a limited extent, and do not develop into epidemics. Epidemics develop only when the combinations and progression of the right sets of conditions occur. These include appropriate temperature, moisture, and wind or insect vector coinciding with the susceptible stage or stages of the plant and with the production, spread, inoculation, penetration, infection, and reproduction of the pathogen.

Thus, for an epidemic to develop, the small amount of original or primary inoculum of the pathogen must be carried by wind or vector to some of the crop plants as soon as they begin to become susceptible to that pathogen. The moisture and temperature must then be appropriate for germination or infection to take place. After infection, the temperature must be favorable for rapid growth and reproduction of the pathogen (short incubation period, short infection cycle) so that numerous new spores will appear as quickly as possible. The moisture (rain, fog, dew) then must be sufficient and should last long enough for the abundant release of spores. Winds of the proper humidity and velocity, blowing toward the susceptible crop plants, must then pick up the spores and carry them to the plants while the latter are still susceptible. Most plant disease epidemics spread from south to north in the northern hemisphere and from north to south in the southern hemisphere. Because the warmer weather and growth seasons also move in the same direction, the pathogens constantly find plants in their susceptible stage as the

season progresses.

In each new location, however, the same set of favorable moisture, temperature, and wind or vector conditions must be repeated so that infection, reproduction, and dispersal of the pathogen can occur as quickly as possible. Furthermore, these conditions must be repeated several times within each location so that the pathogen can multiply, increasing the number of infections it causes on the host plants. These repeated infections usually result in the destruction of almost every plant within the area of an epidemic, although the uniformity of the plants and the size of the area of cultivation, along with the prevailing weather, determine the final spread of the epidemic.

Fortunately, the most favorable combinations of conditions for disease development do not occur very often over very large areas; therefore, spectacular plant disease epidemics that destroy crops over large areas are relatively rare. However, small epidemics involving the plants in a field or a valley occur quite frequently. With many diseases, e.g., potato late blight, apple scab, and cereal rusts, the environmental conditions seem usually to be favorable, and disease epidemics would occur every year were it not for the control measures (chemical sprays, resistant varieties, and so on) employed annually to avoid such epidemics.