Lesson 4 Osteology

The term skeleton is applied to the framework of hard structures, which supports and protects the soft tissues of animals. In the descriptive anatomy of the higher animals it is usually restricted to the bones and cartilages, although the ligaments which bind these together might well be included.

The axial skeleton comprises the vertebral column, ribs, sternum, and skull.

The appendicular skeleton includes the bones of the limbs.

The splanchnic or visceral skeleton consists of certain bones developed in the substance of some of the viscera or soft organs, e.g., the os penis of the dog and the OS cordis of the ox.

The bones are commonly divided into four classes according to their shape and function.

(1) Long bones (Ossa longa) are typically of elongated cylindrical form with enlarged extremities. They occur in the limbs, where they act as supporting columns and as levers. The cylindrical part, termed the shaft or body (Corpus), is tubular, and incloses the medullary cavity, which contains the medulla or marrow.

(2) Flat bones (Ossa plana) are expanded in two directions. They furnish sufficient area for the attachment of muscles and afford protection to the organs, which they cover.

(3) Short bones (Ossa brevia), such as those of the carpus and tarsus, present somewhat similar dimensions in length, breadth, and thickness. Their chief function appears to be that of diffusing concussion. Sesamoid bones, which are developed in the capsules of some joints or in tendons, may be included in this group. They diminish friction or change the direction of tendons.

(4) Irregular bones (Ossa irregularia). This group would include bones of irregular shape, such as the vertebrae and the bones of the cranial base; they are median and unpaired. Their functions are various and not as clearly specialized as those of the preceding classes.

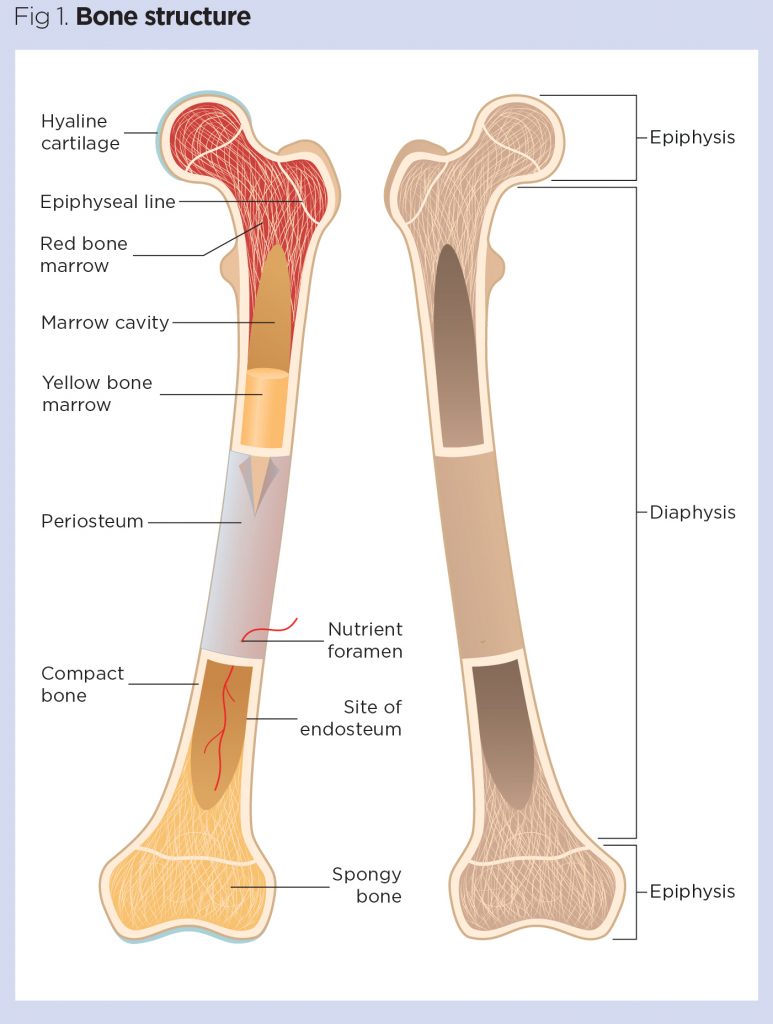

Bones consist chiefly of bone tissue, but considered as organs they present also an enveloping membrane, termed the periosteum, the marrow, vessels, and nerves. The architecture of bone can be studied best by means of longitudinal and transverse sections of specimens, which have been macerated to remove most of the organic matter. These show that the bone consists of an external shell of dense compact substance, within which the more loosely arranged spongy substance be. In tyjDical long bones, the shaft is hollowed to form the medullary cavity (Cavum medullare). The compact substance (Substantia compacta) differs greatly in thickness in various situations, in conformity with the stresses and strains to which the bone is subjected. In the long bones, it is thickest in or near the middle part of the shaft and thins out toward the extremities. On the latter, the layer is very thin, and is especially dense and smooth on joint surfaces. The spongy substance (Substantia spongiosa) consists of delicate bony plates and spicules, which run in various directions and intercross. These are definitely arranged with regard to mechanical requirements, so that systems of pressure and tension plates can be recognized, in conformity with the lines of pressure and the pull of tendons and ligaments respectively. The intervals between the plates are occupied by marrow, and are termed marrow spaces (Cellulse meduUares). The spongy substance forms the bulk of short bones and of the extremities of long bones; in the latter it is not confined to the ends, but extends a variable distance along the shaft also. Some bones contain air spaces within the compact substance instead of spongy bone and marrow, and hence are called pneimiatic bones (Ossa pneumatica).