Proposal and Report Writing

How to write a research proposal

Date published May 2, 2019 by Shona McCombes. Date updated: January 13, 2020

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will do the research. The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals should contain at least these elements:

There may be some variation in how the sections are named or divided, but the overall goals are always the same. This article takes you through a basic research proposal template and explains what you need to include in each part.

Table of contents

Purpose of a research proposal

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal to get your thesis or dissertation plan approved.

All research proposals are designed to persuade someone — such as a funding body, educational institution, or supervisor — that your project is worthwhile.

| Relevance | Convince the reader that your project is interesting, original and important |

| Context | Show that you are familiar with the field, you understand the current state of research on the topic, and your ideas have a strong academic basis |

| Approach | Make a case for your methodology, showing that you have carefully thought about the data, tools and procedures you will need to conduct the research |

| Feasibility | Confirm that the project is possible within the practical constraints of the programme, institution or funding |

How long is a research proposal?

The length of a research proposal varies dramatically. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations and research funding are often very long and detailed.

Although you write it before you begin the research, the proposal’s structure usually looks like a shorter version of a thesis or dissertation (but without the results and discussion sections).

Download the research proposal template

Title page

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your name

- Your supervisor’s name

- The institution and department

Check with the department or funding body to see if there are any specific formatting requirements.

Abstract and table of contents

If your proposal is very long, you might also have to include an abstract and a table of contents to help the reader navigate the document.

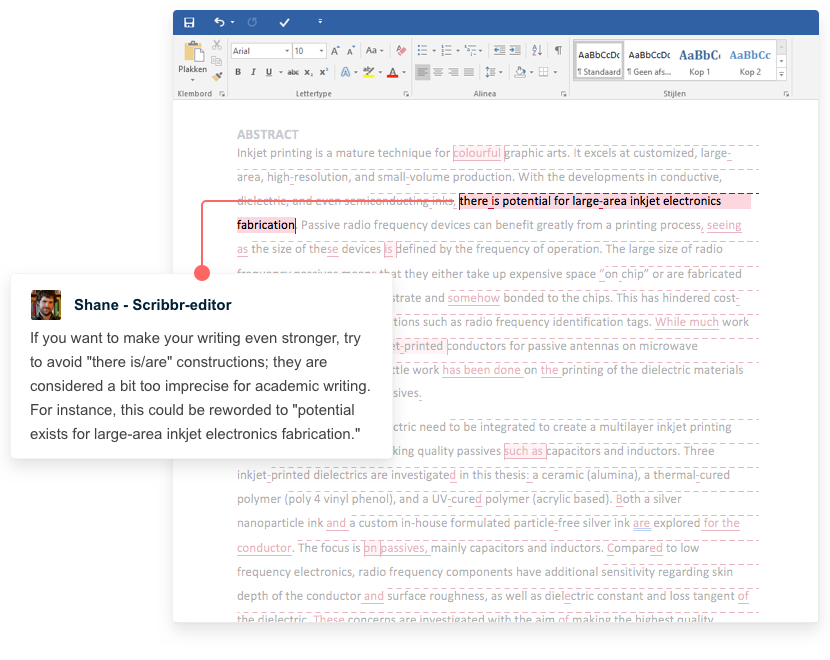

Receive feedback on language, structure and layout

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Grammar

- Style consistency

Introduction

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project, so make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why. It should:

- Introduce the topic

- Give background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research question(s)

Some important questions to guide your introduction include:

- Who has an interest in the topic (e.g. scientists, practitioners, policymakers, particular members of society)?

- How much is already known about the problem?

- What is missing from current knowledge?

- What new insights will your research contribute?

- Why is this research worth doing?

If your proposal is very long, you might include separate sections with more detailed information on the background and context, problem statement, aims and objectives, and importance of the research.

Literature review

It’s important to show that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review convinces the reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said.

In this section, aim to demonstrate exactly how your project will contribute to conversations in the field.

- Compare and contrast: what are the main theories, methods, debates and controversies?

- Be critical: what are the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches?

- Show how your research fits in: how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize the work of others?

If you’re not sure where to begin, read our guide on how to write a literature review.

Research design and methods

Following the literature review, it’s a good idea to restate your main objectives, bringing the focus back to your own project. The research design or methodology section should describe the overall approach and practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| Research type |

|

| Sources |

|

| Research methods |

|

| Practicalities |

|

Make sure not to simply write a list of methods. Aim to make an argument for why this is the most appropriate, valid and reliable approach to answering your questions.

Implications and contribution to knowledge

To finish your proposal on a strong note, you can explore the potential implications of the research for theory or practice, and emphasize again what you aim to contribute to existing knowledge on the topic. For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving processes in a specific location or field

- Informing policy objectives

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific assumptions

- Creating a basis for further research

Reference list or bibliography

Your research proposal must include proper citations for every source you have used, and full publication details should always be included in the reference list. To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator.

In some cases, you might be asked to include a bibliography. This is a list of all the sources you consulted in preparing the proposal, even ones you did not cite in the text, and sometimes also other relevant sources that you plan to read. The aim is to show the full range of literature that will support your research project.

Research schedule

In some cases, you might have to include a detailed timeline of the project, explaining exactly what you will do at each stage and how long it will take. Check the requirements of your programme or funding body to see if this is required.

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review |

|

20th February |

| 2. Research design planning |

|

13th March |

| 3. Data collection and preparation |

|

24th April |

| 4. Data analysis |

|

22nd May |

| 5. Writing |

|

17th July |

| 6. Revision |

|

28th August |

Budget

If you are applying for research funding, you will probably also have to include a detailed budget that shows how much each part of the project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover, and only include relevant items in your budget. For each item, include:

- Cost: exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification: why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source: how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs: do you need to go to specific locations to collect data? How will you get there, how long will you spend there, and what will you do there (e.g. interviews, archival research)?

- Materials: do you need access to any tools or technologies? Are there training or installation costs?

- Assistance: do you need to hire research assistants for the project? What will they do and how much will you pay them? Will you outsource any other tasks such as transcription?

- Time: do you need to take leave from regular duties such as teaching? How much will you need to cover the time spent on the research?

Revisions and Proofreading

As in any other piece of academic writing, it’s essential to redraft, edit and proofread your research proposal before you submit it. If you have the opportunity, ask a supervisor or colleague for feedback.

For the best chance of approval, you might want to consider using a professional proofreading service to get rid of language errors, check your proposal’s structure, and improve your academic style.