Hemostasis and bleeding disorders

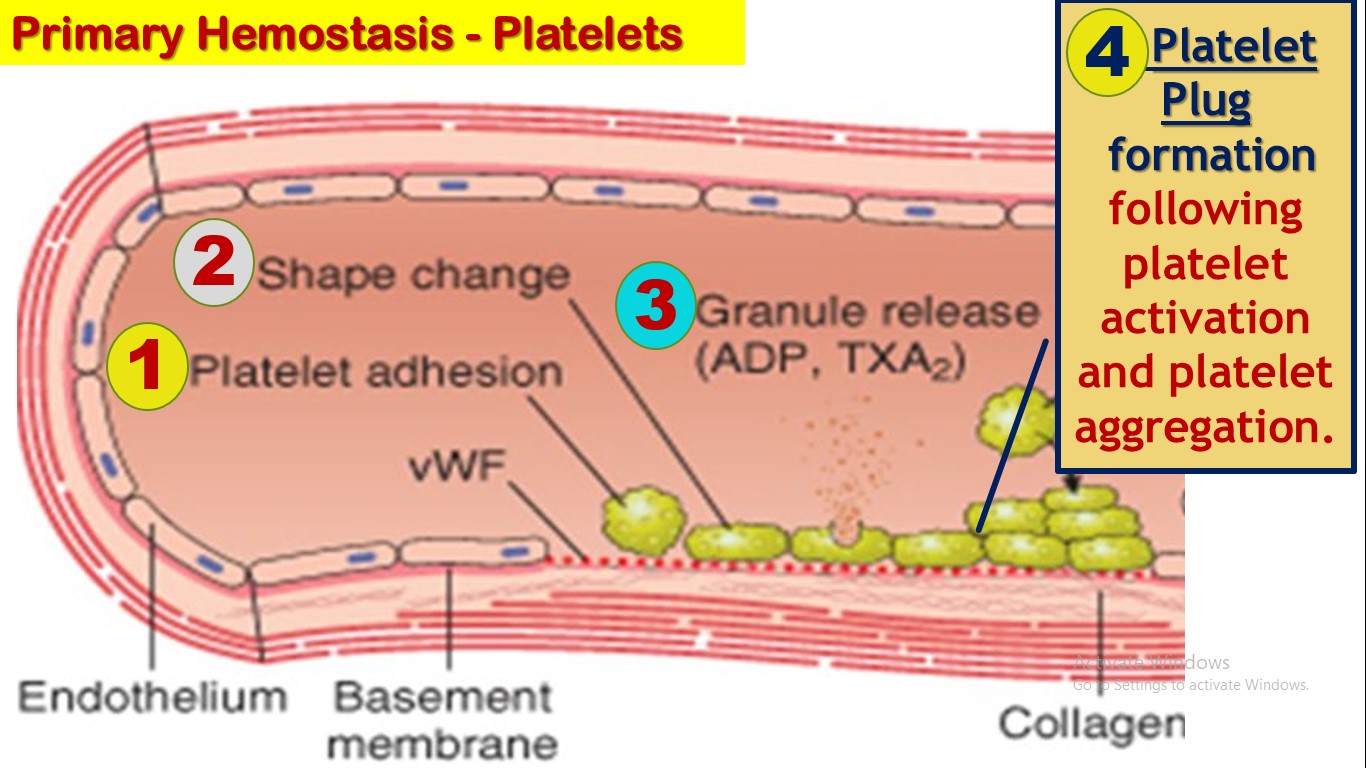

Thrombocytes (also known as platelets) are formed in the bone marrow from megakaryocytes, which are extremely large cells of the hematopoietic series in the marrow; the megakaryocytes fragment into the minute platelets either in the bone marrow or soon after entering the blood, especially as they squeeze through capillaries. The normal concentration of platelets in the blood is between 150,000 and 300,000 per microliter. Immediately after a blood vessel has been cut or ruptured, hemostasis is achieved by several mechanisms: (1) vascular constriction, (2) formation of a platelet plug (primary hemostasis), and (3) formation of a blood clot as a result of blood coagulation (secondary hemostasis). Secondary hemostasis is achieved by activation of clotting factors (cascade) a fibrin mehwork to stabilize the platelet plug. . Most of these factors are synthesized by the liver.

The body has endogenous anticoagulation proteins that play a vital to dissolve these clots. When a clot is formed, a large amount of plasminogen is trapped in the clot along with other plasma proteins. This will not become plasmin or cause lysis of the clot until it is activated. The injured tissues and vascular endothelium very slowly release a powerful activator called tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) that a few days later, after the clot has stopped the bleeding, eventually converts plasminogen to plasmin, which in turn removes the remaining unnecessary blood clot. Excessive bleeding can result from deficiency of any one of the blood-clotting mechanisms. Three particular types of bleeding tendencies are discussed here: bleeding caused by (1) vitamin K deficiency, (2) hemophilia, and (3) thrombocytopenia

(platelet deficiency).

At the end of the lesson students will be able to learn

1. Role of Platelets in primary hemostasis

2. Clotting cascade and hemostasis

3. Clot retraction

4. Antocoagulation

5. Blood Tests to ivestigate hemostasis

6. Hemophilia A and B

7. Thromboembolic Conditions