Emergence of the League of Nations

FOCUS

After the First World War the overriding concern was to avoid repeating conflict on a global scale. A League of Nations was therefore created, intent on solving international problems. But by 1939 the League had collapsed and the world faced yet another conflict of even greater proportions.

In this part of the topic you will study the following:

The League of Nations, its make-up and impact, weaknesses and strengths.

Diplomacy outside the League in the 1920s and the reasons for optimism over a peaceful Europe.

How the League declined in the 1930s and its failure to prevent war in 1939.

The formation and Covenant of the League of Nations

Although there was agreement on a League being formed in 1918, there was disagreement about what kind of organization it should be. President Wilson wanted the League of Nations to be like a world parliament where representatives of all nations could meet regularly to decide on any matters that affected them all. Many British leaders thought the best League would be a simple organization that would just get together in emergencies. France proposed a strong League with its own army. It was President Wilson who won. He insisted that discussions about a League should be a major part of the peace treaties and in 1919 he took personal charge of drawing up plans for the League. By February he had drafted a very ambitious plan:

All the major nations would join the League.

They would disarm.

If they had a dispute with another country, they would take it to the League. They promised to accept the decision made by the League.

They also promised to protect one another if they were invaded. This was called the Covenant, and all countries joining the League had to sign this.

If any member did break the Covenant and go to war, other members promised to stop trading with that country and to send troops if necessary to force it to stop fighting.

Wilson’s hope was that CITIZENS of all countries would be so much against another conflict that this would prevent their leaders from going to war. Many politicians had grave doubts about Wilson’s plans, and Wilson’s own arrogant style did not help matters. He acted as if only he knew the solutions to Europe’s problems. Even so, most people in Europe were prepared to give Wilson’s suggestions a try. They hoped that no country would dare invade another if they knew that the USA and other powerful nations of the world would stop trading with them or send their armies to stop them. In 1919 hopes were high that the League, with the United States in the driving seat, could be a powerful peacemaker.

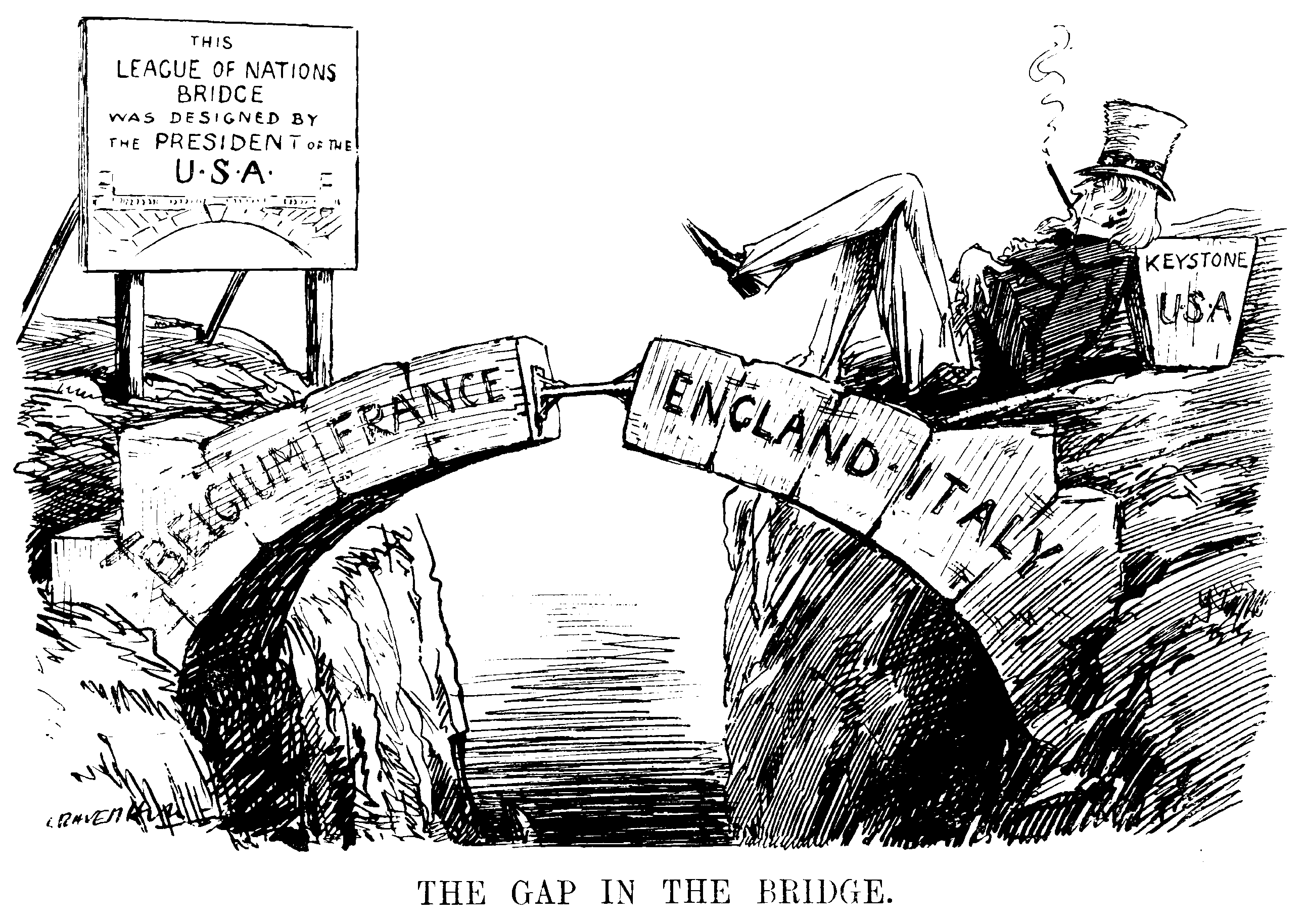

Membership of the League and how it changed

Absence of the USA Of course the USA could only be in the driving seat of the League if it belonged to it. Back in the USA, Wilson was facing major problems. He needed the approval of Congress to join the League and in the USA this idea was not popular. The USA did not want what they referred to as ‘European entanglements’. European countries should now sort out their own problems. Wilson toured the USA to put his arguments to the people, but when Congress voted in 1919 he was defeated. Despite serious illness he continued to press for the USA to join the League. He took the proposal back to Congress again in March 1920 but was defeated again. When the League opened for business in January 1920 the American chair was empty. The USA never joined. It was a bitter disappointment to Wilson and a body blow to the League.

Who was in the League and how was the League supposed to work?

In the absence of the USA, Britain and France were the most powerful countries in the League. Italy and Japan were also permanent members of the Council, but throughout the 1920s and 1930s it was Britain and France who usually guided policy. Any action by the League needed their support. However, both countries were poorly placed to take on this role. Both had been weakened by the First World War. Neither country was quite the major power it had once been. Neither of them had the resources to fill the gap left by the USA. Indeed, some British politicians said that, had they foreseen the American decision, they would not have voted to join the League either. They felt that the Americans were the only nation with the resources or influence to make the League work. In particular, they felt that TRADE SANCTIONS would only work if the Americans applied them. For the leaders of Britain and France, the League posed a real problem. They were the ones who had to make it work, yet even at the start they doubted how effective it could be. Both countries had other priorities. British politicians, for example, were more interested in rebuilding British trade and looking after the British Empire than in being an international police force. France’s main concern was still Germany. It was worried that without an army of its own the League was too weak to protect France from its powerful neighbour. It did not think Britain was likely to send an army to help it. This made France quite prepared to bypass the League if necessary in order to strengthen its position against Germany.

The organisation and powers of the League

The Covenant laid out the League’s structure and the rules for each of the bodies within it

The contribution of the League to peace in the 1920s

Throughout the 1920s the League of Nations was called upon to help sort out international disputes. In 1921, for example, the League helped to solve a dispute between Poland and Germany over the territory of Upper Silesia. League troops took temporary control of the area and the League organised a vote of the people who lived there to decide which state they wanted to be part of. The industrial areas voted mainly for Germany, rural areas for Poland. The League divided the region along these lines, with safeguards for co-operation over power and water supplies in the border areas. Both Poland and Germany accepted the final result of the vote. Similarly, in 1920, both Sweden and Finland claimed the right to the Aaland Islands. The League investigated the issue and the territory was given to Finland. Sweden accepted the decision. And in 1925 Greece invaded Bulgaria. The League of Nations ordered the Greeks to withdraw, and they did. In addition, some of the League’s agencies did extremely important humanitarian work. For example, hundreds of thousands of refugees and prisoners of war were returned to their home countries. Indeed, the later 1920s seemed a time of promise in world affairs. In 1925 Germany signed the Locarno Treaties and appeared to accept the Treaty of Versailles (the Locarno agreements sought to clarify the European borders and gave France some guarantee of border security). Germany was invited to join the League of Nations in 1926. In 1928 most of the world’s major powers signed the Kellogg– Briand Pact, agreeing not to use force as a way of settling international disputes. There was much to be optimistic about. However, when in 1920 Poland invaded Vilna, the capital of Lithuania, the League’s protestations were ignored. This illustrated the limited nature of the League’s actual powers to enforce its decisions, even when these decisions involved smaller nations. But the success of the League was always going to be measured by how well it stood up to a major power acting aggressively. In 1923 Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy, invaded the Greek island of Corfu as part of a dispute with Greece. Mussolini was clearly the aggressor, but the League sided with him. nThe Greeks even had to pay Italy compensation. Cracks in the League’s strengths were beginning to show.

Diplomacy outside the League of Nations in the 1920s

During the 1920s not all international diplomacy took place as a result of the League of Nations. There were some key treaties and alliances agreed outside the League.

The Locarno treaties A whole series of Treaties were drawn up at Locarno in Switzerland in autumn 1925 and then signed in London in December of that year. These treaties involved leading European countries, including Germany and the USSR who were not in the League of Nations at that time. Some of the treaties were agreements to settle disputes peacefully. However, the main treaty involved France, Belgium and Germany who promised not to invade each other, and Germany agreed to keep its troops out of the Rhineland. In other words, Germany was accepting the territorial terms of the Treaty of Versailles on her western front. However, there was no similar firm promise on her eastern front.

The Kellogg–Briand Pact, 1928 On the initiative of US Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, and the French foreign minister, Aristide Briand, 61 countries signed the Kellogg–Briand Pact. Each country promised not to use war as a way of solving international disputes. It seemed like a triumph of pacifism and common sense. However, in retrospect it could be seen as a weakening of the League of Nations whose apparent strength lay in the belief in COLLECTIVE SECURITY. No sanctions were agreed upon against countries which ignored the agreement in the future. Thus in the late 1920s there was an air of optimism surrounding European diplomacy. However, very soon in the 1930s all this changed as DICTATORSHIPS tore up agreements and treaties.